When LOBBY HERO premiered Off-Broadway in 2001, New York magazine reviewer John Simon opened his critique of the play by describing playwright Kenneth Lonergan first and foremost as the man who wrote the year's best movie.

It's fitting, though. Over his career, Lonergan has doled out his work sparingly, but evenly, between the screen and the stage, with each medium informing the other. In Milwaukee, the comparison will be easier than ever this fall, with MCT's production of LOBBY HERO overlapping with the limited release of Manchester by the Sea, written and directed by Lonergan.

If full Lonergan immersion's your game -- or if you just want to know a little more about the guy before you come and see the show -- here's a breakdown of the most significant works he's written, for both film and the stage.

THIS IS OUR YOUTH (1996)

Lonergan's big breakthrough, THIS IS OUR YOUTH is set in the early '80s, tracking 48 hours in the lives of three lost young souls who've gotten their hands on $15,000 (stolen from a tycoon daddy, of course). As the first example of Lonergan's trademark balance of the dramatic and the comedic, with a focus on issues of materialism and adolescent maturity, the show was a quick success, receiving acclaim, a second Off-Broadway staging in 1998, and a series of productions in London's West End in quick succession.

The original production featured Mark Ruffalo in one of his first-ever professional roles, launching his career and a longtime partnership with Lonergan. Its recent revival -- on Broadway for the first time, in 2014 -- featured Michael Cera in Ruffalo's role, alongside Kieran Culkin and Tavi Gevinson.

A memory play in more ways than one, THE WAVERLY GALLERY depicts Gladys Green, an elderly woman slowly dying of Alzheimer's, seen through the eyes of her narrator grandson. Again displaying Lonergan's skill in comic drama, the play was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama, and picked up four major awards for the performance of Eileen Heckart, the actor portraying Gladys.

After co-writing the film Analyze This with Harold Ramis and Peter Tolan in 1999, Lonergan's next project was as big a breakthrough in the world of film as THIS IS OUR YOUTH had been on the stage. Reuniting Lonergan with Mark Ruffalo, the film follows an estranged brother and sister (Ruffalo and Laura Linney). They reunite when he returns to the Catskills community where they grew up, but his arrival subtly throws her life into disarray, slowly forcing them into conflict.

Lonergan directed the film, as well as wrote the screenplay, and critics took note. Many placed the film on their best-of lists for 2000, specifically citing Lonergan's "bottomless dialogue" and the film's emphasis on making everyday problems as compelling as high drama. Before the awards season was over, You Can Count On Me would pick up dozens of wins and nominations, including two Oscar noms and two awards at Sundance including the Grand Jury Prize.

Lonergan directed the film, as well as wrote the screenplay, and critics took note. Many placed the film on their best-of lists for 2000, specifically citing Lonergan's "bottomless dialogue" and the film's emphasis on making everyday problems as compelling as high drama. Before the awards season was over, You Can Count On Me would pick up dozens of wins and nominations, including two Oscar noms and two awards at Sundance including the Grand Jury Prize.

THE STARRY MESSENGER (2009)

The '00s marked a creative drought for Lonergan (partly for reasons discussed in the next entry), but he would finally return to the stage in 2009 with THE STARRY MESSENGER, his first fully produced play since LOBBY HERO opened in 2001 and his debut as a director of his own work. A star vehicle -- pun only slightly intended -- for Matthew Broderick, MESSENGER orbits around a 40-something married man who works at the Hayden Planetarium and unexpectedly connects with a single mother.

MESSENGER didn't receive the same adulation as Lonergan's earlier works for the stage, but his ear for dialogue and unique mix of comedy and drama was once again highlighted even in mixed reviews (a fate shared by Lonergan's most recent play, HOLD ON TO ME DARLING, which opened earlier this year at Atlantic Theater Company).

MESSENGER didn't receive the same adulation as Lonergan's earlier works for the stage, but his ear for dialogue and unique mix of comedy and drama was once again highlighted even in mixed reviews (a fate shared by Lonergan's most recent play, HOLD ON TO ME DARLING, which opened earlier this year at Atlantic Theater Company).

After the success of You Can Count On Me, Lonergan had a number of writing and co-writing gigs in Hollywood, including the screenplays for the sequel to Analyze This and Scorsese's Gangs of New York. But his most anticipated film was Margaret, a drama starring Anna Paquin about a teenage girl who believes she helped cause a traffic accident that killed a woman.

Filmed in 2005, Margaret was intended for release in 2007, but Lonergan and the film's studio, Fox Searchlight Pictures, disagreed on the film's runtime. Fox insisted on a tight 150 minutes or less, while Lonergan's own edit was closer to three hours. The legal battle ate up years, and ultimately concluded with two versions of the film being released -- a 150-minute edit, which hit theaters in limited release in 2011 and was commercially unsuccessful, and an extended cut released on DVD in 2012 completed by Lonergan. Despite all the drama, the final release of the film received raves from many critics, and Lonergan himself says he's happy with the final cut.

Filmed in 2005, Margaret was intended for release in 2007, but Lonergan and the film's studio, Fox Searchlight Pictures, disagreed on the film's runtime. Fox insisted on a tight 150 minutes or less, while Lonergan's own edit was closer to three hours. The legal battle ate up years, and ultimately concluded with two versions of the film being released -- a 150-minute edit, which hit theaters in limited release in 2011 and was commercially unsuccessful, and an extended cut released on DVD in 2012 completed by Lonergan. Despite all the drama, the final release of the film received raves from many critics, and Lonergan himself says he's happy with the final cut.

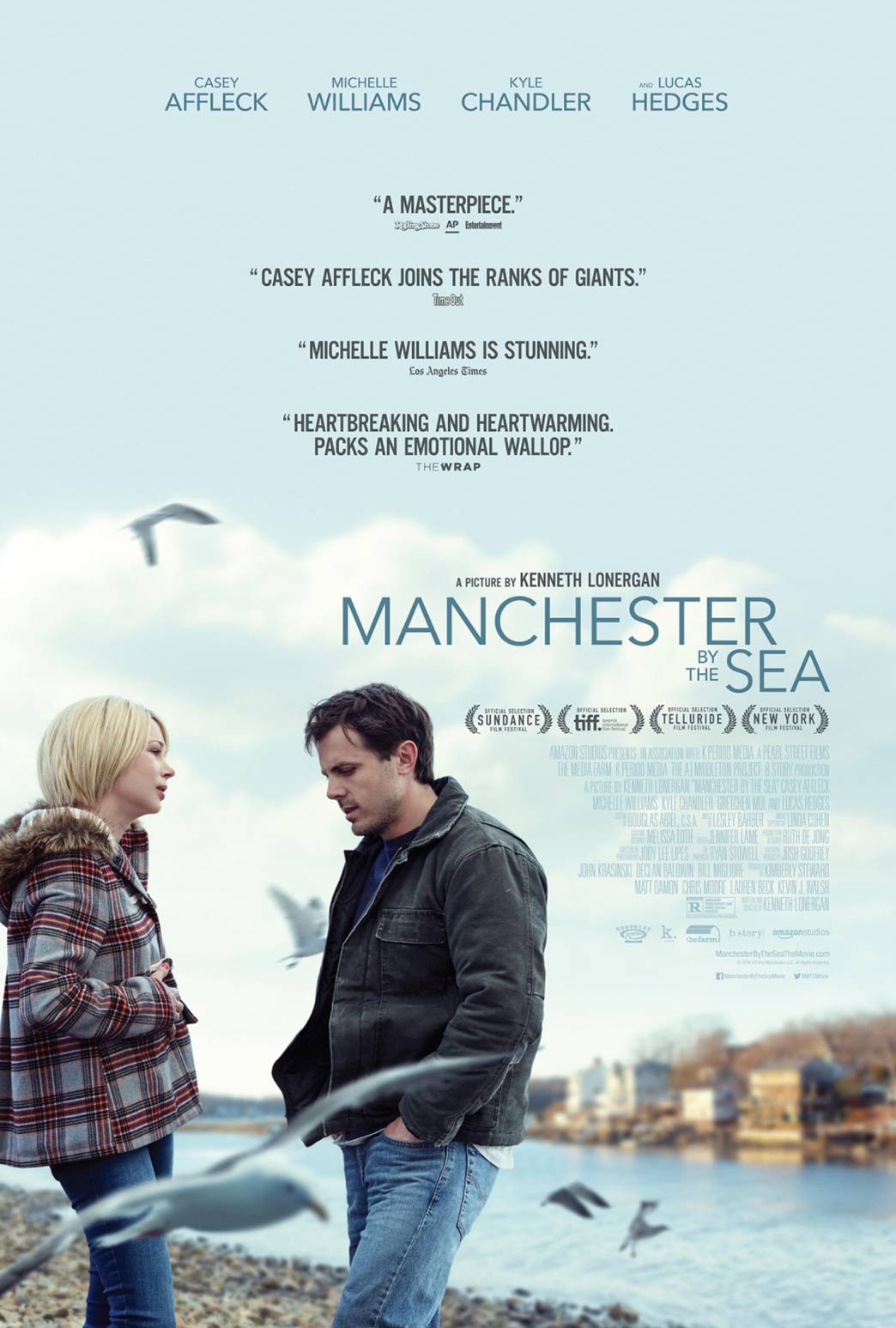

No such disputes marred the development of Lonergan's latest film, his third as a writer/director. Manchester by the Sea, set to be released in select theaters on Nov. 18 before a wider release in December, tells the story of a self-isolated man (Casey Affleck) who must unexpectedly return to his hometown to care for his nephew when his brother dies, and in the process revisits his greatest personal tragedy.

Originally, Lonergan was only booked to write the script -- the original idea came from producer Matt Damon, who had planned to direct himself and recruited Lonergan for the screenplay. But scheduling conflicts shifted Lonergan into the director's chair as well, and he would shape the film with his own vision.

Buoyed by strong advance reviews, early acclaim (a Hollywood Screenwriter Award for Lonergan and five Gotham Award nominations) and lots of Oscar buzz, Manchester looks poised to make this Lonergan's year. All the more reason to catch MCT's LOBBY HERO now -- before all the hype kicks in.